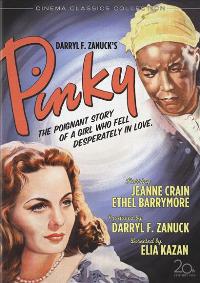

Pinky

The sinister role that skin color plays in a society that

limits its perception to it is undoubtedly highlighted in films such as

“Pinky”. Exploring the experiences of a

black woman so light that she passes for white forces one to really examine

definitions of race and the rigidity of perception in a racially biased

environment. Patricia “Pinky” Johnson

played by Jeanne Crain, returns to the “Deep South” under Jim Crow laws after

graduating from nursing school in Boston.

While in Boston, she lived life as a white woman. She returns to the South because she has, as

she says: “nowhere else to go.”

Her

return is heralded as good news. The

local black community is happy about her arrival because she would be a great

asset to the community due to her medical training. Her grandmother is expecting her to continue

the family tradition of servitude by providing bed-side care to old, dying Miss

Em., and a local black doctor is soliciting her to start a nursing school to

help provide education and training to the young black women of the community

who are high school graduates.

“Pinky”

is conflicted and disgusted by what she has to face. Her grandmother is still providing

washer-woman services to the aging and dying Miss Em., who no longer has any

money to provide any pittance to her servant.

Everyone in town suspects her of “passing” for white “up yonder” and she

is constantly being admonished to stay true to who she is and not deny being

black. This provides an undeniable

conflict for the character because who she is, is a woman who looks white. She has frequent and intense arguments with

her grandmother where she declares that she has been treated like an “equal” in

Boston and does not want to accept the low-class status that she is being

forced into in the South. “Pinky”

determines to leave, however she reluctantly stays out of reverence for her

grandmother’s request.

“Pinky”

bristles at having to accept a servile position. She has several venom-filled exchanges with Miss

Em. while tending to her. She demands

that Miss Em. respect her due to her training as a nurse. She fights back against Miss Em.’s subtle

accusations of theft, her domineering tone of voice and her requests that she

perform servile tasks.

“Pinky’s”

past finally comes back to haunt her.

Her white boyfriend that she had in Boston comes looking for her after

receiving a mysterious telegram about her, confirming to her grandmother that

she was living a lie in Boston. She

confesses to her boyfriend that she is really black. They reconcile and make plans to be reunited

and marry after she finishes working for Miss Em.

In

one very illuminative scene, the viewer truly catches a glimpse of the thin

racial line that the character has to walk, and is exposed to the strong

enticement that the character faces to pass for white. “Pinky” walks into a fabric store and is

immediately waited upon by a white sales woman.

She is shown the best fabric that the store has. Her money is accepted for payment until it is

pointed out by another white patron that she is actually “colored”. Instantly, she is transported into second-class

status and is ganged up on by the patron, the sales woman and the shop owner

and is accused of having stolen the money she is using to pay for the fabric.

The

film toned down the harshness of racism in the “Deep South”. Things turned out surprisingly “well” for the

young black woman who looks white. She

is made heir to her grandmother’s “employer’s” property and is victorious over Miss

Em.’s legal relatives in court as they fight over her will, a rare experience

for blacks in the “Deep South”. Due to

the white woman’s benevolent bequeathal, the black community is provided with

a nursing training center, hospital and nursery in the home of a former slave

owner. “Pinky’s” boyfriend, played by

William Lundigan is surprisingly understanding of being lied to and deceived by

his black lover and still wants to marry her and keep their racial differences

a secret.

“Pinky’s”

grandmother, Dicey Johnson is played by Ethel Waters who does an excellent job

of portraying the servile, worshipful mentality of many blacks who worked for

whites. She encourages her granddaughter

to stay and work for the family’s owner, even though she sent her away to school

in order to improve her station in life.

She relishes any scrap she receives from her owner. She is “proud” to be left with her deceased

owners clothes and does not complain about working for no pay.

“Pinky”

was a bold piece for the time it was made in 1949. It shattered many societal taboos and was

banned in some areas of the country for its “suggestive influence”. Some objected to the onscreen portrayal of

miscegenation and for some uncomfortable sexual situations. The movie director Elia Kazan had a strong

history of making movies that tugged at the social fabric of society. “Pinky” was Elias second film and was one of

the first films in America to address racism against blacks. The film does a wonderful job of bringing

society face to face with the juxtaposed lives of whites and blacks in

America. It provides an artful and

palatable way for the larger society to face its demons. “Pinky” is a thought provoking, classic movie

whose themes are still relevant to society today. In a society still struggling with

inter-racial unions, legal justice for blacks and providing a level playing

field for all its members of society, a contemporary review of this movie’s

themes would be a relevant, useful and welcome commentary.

Published: www.democracychronicles.com/pinky-skin-color-identity

Published: www.democracychronicles.com/pinky-skin-color-identity

No comments:

Post a Comment